In Our Own Words - National Weather Service Heritage

In Our Own Words...

As the National Weather Service celebrates its 150th Anniversary in 2020, NWS employees and retirees are sharing their own memories and thoughts about our heritage. Read their stories in their own words below.

We at the NWS Heritage Project can’t complete such an enormous task without you! Whether you’re a current or former employee of the NWS, your memories and stories help us better understand the history of our agency, how we got to where we are today, and where we will go next. If you’re interested in writing a story or even providing us with some background information on an event, technology, era, or other memory from your time at the NWS, please check out the following guide and forms:

Alexander MacDonald

Prototyping a Technological Cornerstone of the Modernization Era

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website.

One of the most crucial elements of the Modernization era of the National Weather Service was the improvement of forecasting and warning services — can we issue forecasts earlier? Can the forecasts be more accurate? How do we maximize our ability to protect life and property? When it came to technological development in this area, many people were instrumental in revolutionizing the forecasting systems, including Alexander “Sandy” MacDonald.

MacDonald joined the National Weather Service in 1975 working in the Western Region’s Scientific Services Division before moving to NOAA’s Environmental Research Laboratory in 1980. Later in his career he served as Director of NOAA’s largest research laboratory, the Earth System Research Lab in Boulder, Colorado. From the beginning, he acknowledged that the computer and tech revolution had arrived, and pushed for the creation of an integrated system that would incorporate all of the old technologies to improve weather warnings. Working to that end, MacDonald and his team had to construct several prototypes of the new system in order to show Congress what they were trying to do, certainly no small feat. Those prototypes eventually evolved into AWIPS, an integrated processing system that became a technological cornerstone of the Modernization era.

Here are two excerpts from his interview recorded October 2010:

On the partnership between research and operations:

“You had this coming together of two parts of NOAA. One of them is the research part saying, ‘we want to help you build this’ and one is the operational part, where you have a visionary and leader like [NWS Director] Dick Hallgren who knows the system and says, ‘I want to build a National Weather Service that is modernized and uses all the data in the right way and what I expect to get out of this is a big improvement in our ability to put out weather warnings.’ And nobody can argue with that. That’s clearly a government function: protect the people.”

On the approach of building early prototypes:

“We're going to build a version of this system that, even in the first year, it really is pretty limited and it isn’t anything like what we ultimately want. We're going to actually get software people and build one. Nowadays that’s called rapid prototyping and I think it's the absolute key to the fact that we really progressed pretty fast.”

Resources and Additional Reading:

-

Full interview transcript and Audio recording with Alexander MacDonald, October 2010 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/alexander-e-sandy-macdonald

Carl Bullock

Focusing AWIPS on Severe Weather Operations

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website.

Carl Bullock began working for the National Weather Service as a meteorological intern when he was fresh out of college in 1973 — little did he know he had joined the NWS just in time to play a role in one of the agency’s most important eras: the Modernization.

After holding various different positions in a few different forecast offices, Bullock joined the Program for Regional Observing and Forecast Services (PROFS), a team that was working to improve the existing Automation of Field Operations and Services (AFOS), a technology that connected all field offices to a network of forecast and weather map data. Bullock’s role was to filter through the emerging set of requirements for AWIPS, a developing processing system that would eventually replace AFOS, and had to juggle various requirements from across NOAA, NWS, and even Congress while keeping the system’s focus on severe weather operations. AWIPS, an interactive computer system that integrates all meteorological and hydrological data with satellite and radar imagery, is a technologically-advanced information processing, display, and telecommunications system that is the cornerstone of the National Weather Service modernization and restructuring. By the turn of the century, the AWIPS system was implemented, helping to usher the NWS into the next century.

Here is an excerpt from his interview recorded June 2010:

On what it was like to work at NOAA during the Modernization:

“It's been ... wonderful working in NOAA. I really have enjoyed it. I enjoyed the people I worked with. And enjoyed working with the technology and seeing that. I mean, the changes are just almost unbelievable from the time I started this as a meteorologist intern until I retired. So, it's been very satisfying on -- on those two aspects. I think at the time we put our system in place in 1999, it was arguably the best system in the world for what it -- for what it did. The GFE [Graphical Forecast Editor] is still rather unique. That set of software that allows the forecaster to create a digital representation of the forecast data is still relatively unique. And it's been adopted by a number of countries internationally now. So that ... that's been very gratifying.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcript and audio recording with Carl Bullock, June 2010 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/carl-s-bullock

Chris Stachelski

Here, in his own words, are those of Chris Stachelski, Regional Cooperative Observing and Climate Services Program Manager, NWS Eastern Region, Bohemia, NY.

How An Interest In Weather and A Big Blizzard Triggered A Career Path In Climate and Weather Observations

Most meteorologists got their interest in weather at a very young age, likely from one big storm or a number of storms or by watching cloud formations. Mine was a gradual interest from a series of weather events in the 1980s when I grew up in New Jersey. The oldest memorable one was being getting chased off the boardwalk in Seaside Heights (in the pre-MTV and Jersey Shore days) in July 1983 by a severe thunderstorm that literally sent crowds running – including my family – and getting drenched by the rain. Within a few days I would learn that not far from where my relatives and I were staying a supermarket had lost its roof from the storm because of a tornado, a rare event in New Jersey, especially one rated a F3. The following year my preschool came within feet of being inundated by a major river flood. The next year was Hurricane Gloria. And in the following years came numerous snowstorms that crescendoed in the winter of 1995-1996 with record seasonal snowfall in metropolitan New York City featuring the legendary Blizzard of ’96.

Growing up in the hill country of northwestern New Jersey, the closest National Weather Service office until 1996 was roughly 25 miles away at Newark International Airport. Besides the distance, Newark Airport was nearly 500 feet lower in elevation and far more urbanized and often got much less snow or no snow at all compared to where I lived in many winter storms. Even though this was the closest primary climate site to my house the climate was different enough that my dad used to like to take snow measurements after a decent snowstorm to keep his own records. He started around the Blizzard of ’78 and would write them on a calendar in our garage. When my own interest in weather kept escalating, I also started talking snow measurements and would compare them with my dad. Sometimes we had significantly different amounts. He used a spot that was fairly consistent and far away from most obstructions and about as level as we had on our property for years. Considering he was never a spotter or trained by a meteorologist he actually did pretty good, looking back at it.

I then started to wonder more how snow was measured in the figures shown on the television news at Central Park or the ones in the newspaper from Newark Airport. There was no internet over 25 years ago and learning about weather was confined to books, magazines, newspapers and some television including The Weather Channel. Finally, in the winter of 1994 during a snowstorm, WCBS in New York sent their weatherman Storm Field to Central Park to do a live broadcast of the National Weather Service measuring the official snow. I watched a meteorologist walk out into the grass and take several readings with a measuring stick and come up with an average. That was the official reading. I was thrilled to finally see how ‘it’ was actually done by a professional.

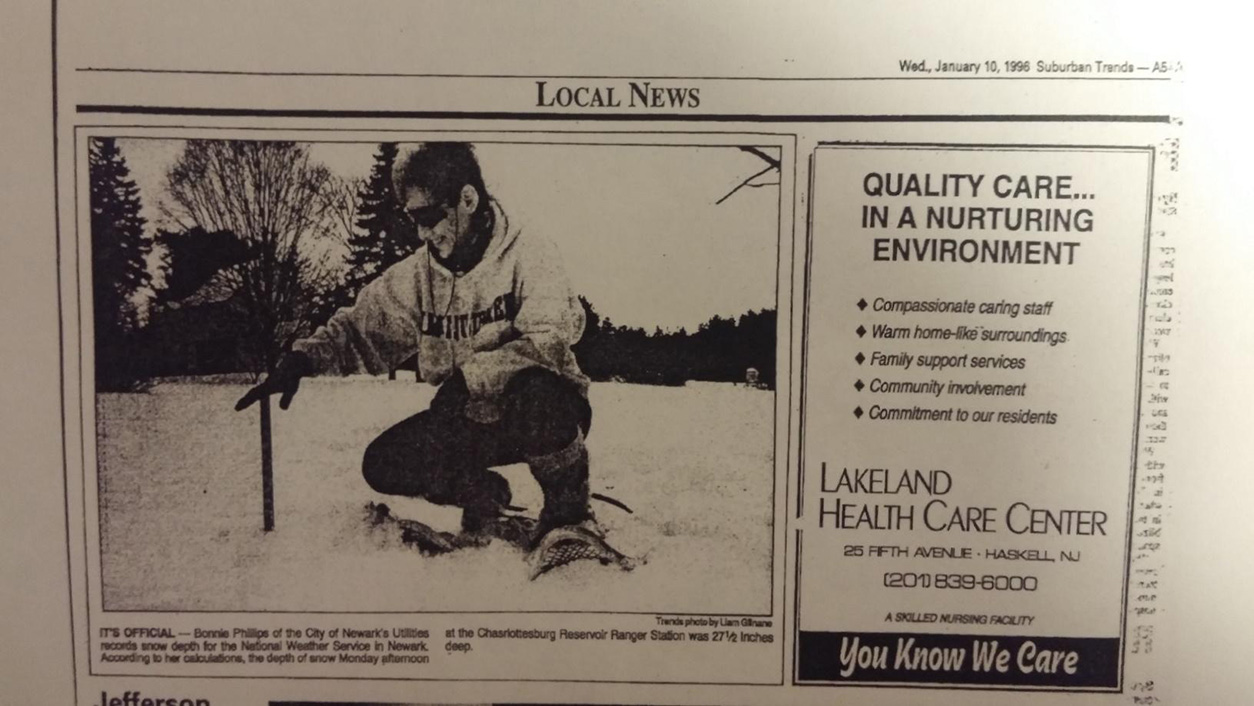

Two years later the Blizzard of ’96 hit. It remains the single largest snowstorm I ever personally witnessed. I measured 29.9 inches of powdery, wind-driven snow after taking 10 readings in different spots. I felt confident in my reading but I watched the news to see of any nearby towns had reports in of how much snow fell. There was no such luck. A few days later my dad obtained the Star-Ledger newspaper in hard copy from a co-worker from the two days after the storm. Newspaper deliveries were cancelled in most areas from the blizzard so obtaining a print copy from that time frame was not easy as most were not delivered. In it was a map with different towns that had measurements obtained by the National Weather Service. One report about 12 miles west from my house said “Charlotteburg, 27 inches.” That area was similar in terrain and I felt even better about my reading as amounts trended up going east in northern New Jersey due to the storm track. The following day a weekly local newspaper was delivered to our house and I looked through that. In the corner was a small photograph that caught my interest. It was a lady measuring snow – at Charlotteburg – and said she took the readings to send into the National Weather Service. I had no idea the National Weather Service had any sort of connection that close to my house to record weather as I assumed their only reports in my area of New Jersey were at Newark and the airports at Morristown and Teterboro. My interest grew further in what this was about.

Finally, the internet and college came along and I was told about the cooperative weather program by a professor. This was what I had seen in the newspaper after the Blizzard of ’96. I was fascinated further. I looked this up online and there were stations all over that had readings close to where I lived that would give me a better idea of how my past snow measurements compared to what was official. I could even look up totals from storms when I was even younger but did not measure how much snow fell. It was a treasure trove of information.

My interest in climate continued through college. My first visit to a National Weather Service office was in 2000 when I visited the Tallahassee, Florida office to work on a project in college for an internship I had. I was tasked to visit there and obtain copies of their local daily and monthly records. In those days records were still kept in a physical ‘record book’ written by typewriter or in WordPerfect and crossed out with a pen when broken at most offices. I took the records for my project and entered them in an electronic file that could be easily updated when they were tied or broken. Later while wandering at the library I found a section that housed government records and came across dozens of books with old weather data in them called “Climatological Data” that went back to 1914. They were for each state or a group of states. I used these for another research project for my synoptic meteorology class. Climatological Data is a publication still produced today that lists the daily and monthly values collected by cooperative observers across the country.

Eventually after graduating college and working in the private sector, I started with the National Weather Service in January 2007. I’ve been involved directly with the climate and cooperative weather programs each day since. My first job was a Meteorologist Intern at the Hanford, California Weather Forecast Office. I would call observers and collect and quality control their data. The Meteorologist-In-Charge along with the forecasters in the office recognized my interest in these programs was well above average and eventually asked me to assist these programs as an assistant focal point. In March 2008 I was promoted to the Las Vegas, Nevada Weather Forecast Office as a forecaster. I eventually became the Climate Focal Point and when our longtime Observing Program Leader retired took over the cooperative weather program for a year and a half due to ongoing vacancies. This is one of the largest geographic areas covered nationally by the program as it covers parts of four states.

In February 2016 I started my current position at Eastern Region Headquarters on Long Island, New York as the program manager for observations and climate services. This position oversees the nearly 1,400 cooperative weather stations in the region including site visits, equipment, awards and other paperwork in addition to data collection and quality control. As part of this position, I oversee the snow measurements in our region at all climate sites. After having graduated from college in Florida in meteorology I will say this is the most unusual thing I could have ended up doing as part of a job. But in a way much of my interest in my younger days now serves me well and guides me in this area. As part of this job I finally had the chance in 2016 to visit Central Park and Newark Airport and see in person how they measure snow and reflect back on my early interest in weather reports from both stations.

I also get the opportunity to visit some of our sites to present awards to observers. I’ve been privileged and honored to present awards to two cooperative observer sites who played a role in my early interest in weather. One of those was to the retired meteorologist from the National Weather Service who surveyed the tornado that spiked my interest in weather back in 1983 who serves as a cooperative observer at his house in South Jersey. The second was to the observers at the Newark Water District who operate three stations for the National Weather Service in North Jersey including Charlotteburg. It was a surreal experience for me to visit the site that first sparked my interest in the cooperative observing program over two decades earlier. Not all meteorologists get the chance to visit the people and places that inspired them early on in their interest in weather. I feel lucky I’ve had this chance and the opportunity to personally thank these observers for their data and services. I likely wouldn’t be writing this article if it wasn’t for them.

Deborah Jones

Here, in her own words, are those of Deborah Jones, Program Analyst for the Rip Currents and Beach Hazards Program at NWS Headquarters in Silver Spring, MD.

“In my thirty plus years with the National Weather Service, I have always looked forward to coming to work primarily for two reasons: first, because of the professionalism and passion of my co-workers for saving lives; and second, because in my position as a Program Analyst for the Rip Currents and Beach Hazards Program, I can directly and indirectly contribute to the saving of lives.

Every day of my, to-date, thirty-three year career at NWSQ has proven to be a wonderful place for me to sink my roots and develop my career. It has afforded me the opportunity to pursue my passionate interest in the physical sciences, and share that knowledge with individuals and the public through the development of lifesaving outreach materials. I have been truly blessed to have worked with equally as passionate and skilled colleagues in the development of these materials. As a life career, my tenure at NWS couldn’t have been more perfect.

I remember the day in 2012, when a woman sent me an email sharing her real life testimonial about the “Break the Grip of the Rip!® video, which I helped to develop. While on vacation in Mexico, she had taken the time to watch the NOAA/NWS “Break the Grip of the Rip! ® video. The time she took to watch this video saved her life. While swimming in the Pacific Ocean, she had gotten caught in a strong rip current which dragged her into rough waves that kept slamming her into rocks. In a desperate moment, she recalled the rip current video she had watched an hour earlier showing her how to escape a rip current. She immediately followed those instructions and got herself out of the rip, away from the dangerous waves, and safely back on the dry beach. She was very grateful to NOAA/NWS for making the rip current video that had shown her how to save her life if caught in a rip current.

Just another day in the office at NWSHQ Marine Branch...and yet, I have received countless phone calls and emails from Chambers of Commerce, beach rental properties, agencies, local citizens in small coastal towns throughout the nation and even internationally asking for help with how to raise the awareness of their local citizens and visitors to surf zone hazards, such as rip currents and dangerous waves that are indigenous to their coastal waters. The gratitude for the outreach materials I send has continually compelled me to keep pursuing the creation of lifesaving messages.

Just another day at the beach...well, yes and no. Yes, in that it is our mission here at NWS to primarily save lives; however, to save a life goes beyond the routine duties of an office job. To know that your daily, routine tasks are contributing both directly and indirectly to saving lives and enhancing the economic viability of the nation can only be summed up as the most perfect routine job that has the most extraordinary impact on society.

Dennis Walts

Bringing Technology From Research and Development to National Use

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website.

As the National Weather Service began moving forward with modernization efforts, it became clear the future of the NWS would involve the development of new technologies. One technology discussed at the time was the Advanced Weather Interactive Processing System (AWIPS) that would replace the Automation of Field Operations and Services (AFOS), a similar and older system. AWIPS, an interactive computer system that integrates all meteorological and hydrological data with satellite and radar imagery, is a technologically-advanced information processing, display, and telecommunications system that is the cornerstone of the National Weather Service modernization and restructuring. AWIPS helps the forecaster prepare and issue more accurate and timely forecasts and warnings. Dennis Walts, longtime NWS employee, played a crucial role in that entire process.

Around the turn of the century, Dennis Walts was sent to Boulder, CO for many reasons -- not only was he tasked with building the AWIPS workstation itself, he also had to integrate all of the new datasets that were going to be a part of the MAR. New and emerging technologies like Doppler Radar, Advanced Guidance Gridded Data, and other surface/satellite data would need to be included. Working with forecasters and programmers, Walts was able to assist in bringing AWIPS technology from research and development all the way to national expansion and use.

Here are two excerpts from his interview recorded in June 2010:

Regarding the challenge of bringing diverse environmental data sets into AWIPS:

“We worked with so many different people and organizations that the coordination of that was probably the biggest challenge. It was an interesting challenge to do all of that coordination, to make sure that, in fact, the datasets that we were getting were going to be part of the modernization, and that the interfaces we were building were going to interface to the real datasets. The real challenge was that so many of the pre-AWIPS datasets were on their own scales, their own coordinate systems. Everything was different.”

On lessons learned throughout the whole process:

“You have to learn by doing. There are a lot of ways to screw this up. I said, we’ve got some pretty smart people here, but we can’t think of all of it. We’ve got to learn by doing. There are a lot of ways to screw it up and we can’t afford to screw it up.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcript and audio recording with Dennis Walts, June 2010 are available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/dennis-s-walts

Doug Sargeant

Ushering NWS Science and Technology Into a New Era

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website.

With the ongoing evolution of technology over the last several decades, it should come as no surprise that technological development became a cornerstone of the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring era. With the help and expertise of people like Doug Sargeant, the NWS was able to usher in an age of innovative science and technology.

After studying meteorology in college, Doug Sargeant became a part of the Global Atmospheric Research Program (GARP), a team that explored and developed technologies such as radiosondes and satellites that could produce surface observations and monitor weather developments. In January of 1970, Doug came to Washington, DC to get federal agencies involved in GARP. It was soon determined that the newly formed NOAA would take the lead. As GARP became GATE, an international collaboration concerned with the development of observational systems, Sargeant was asked to stay on and help get it up and running. Sergeant eventually became the head of systems development at the beginning of the MAR, an era that expedited the development of observational technology. Over the course of the MAR, Sergeant worked to integrate new science and technology into operations at the NWS.

Here is an excerpt from his interview recorded in August 2010:

On his motivation for involvement in the Modernization and Associated Restructuring effort:

“From my standpoint, I have to confess that the things that I most cared about in the restructuring part of the Weather Service were ones that would facilitate getting new science and technology into operations. It wasn't that much about the operations itself and making them more efficient or what have you. It was trying to actually get the science and operations into that stream. So for me, that technology transfer -- science and technology transfer -- was the driving motivation that I was always after.”

Resources and Additional Reading

- Full interview transcript and audio recording with Doug Sargeant, August 2010 are available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/douglas-h-sargeant

Dr. Robert Serafin

Bringing Radar Expertise to the Development of NEXRAD

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website. Reichenbaugh retired in 2018; we are indebted to him for undertaking this important project.

The National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring effort was an enormous undertaking, requiring a lot of moving parts in order to be successful. One of the most crucial parts of this process was the establishment of the National Academies’ National Weather Service Modernization Committee, a team of experts to help guide the agency through the changes ahead. Only the best and brightest were selected for such an important role — enter Dr. Robert Serafin of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR).

Dr. Serafin was recruited for the Committee after a long career in the field of radar meteorology and, later, atmospheric observation. His expertise had previously been sought-after based on his background with Doppler radar technology, and his advice was essential in procuring the technology for the NEXRAD system, one of the agency’s priorities during the MAR.

Here are two excerpts from his interview recorded in June 2010:

On the importance of the Committee to the MAR effort:

“The people who were on that committee were really committed. They came to the meetings. They had an interest in what was going on. They knew technically and scientifically what was going on. We had people who understood the human relations, the employee relations part of it; the committee was strongly committed to human engineering to be sure that the systems that were going to be procured were actually going to do the job and be useful to the engineers, scientists, meteorologists. We had a lot of interactions with the operational people. So something like that, that kind of a committee has a lot of value.”

On being a part of the MAR:

“It wasn’t something easy to do. It’s never easy to do good things, to break away from a paradigm … Politically, there were big challenges. Technically, there were big challenges. Organizationally, internally, externally there were big challenges. I was really happy to be a part of that in a small way.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcript and audio recording of Robert Serafin from June 2010 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/index.php/robert-serafin

Elbert W. “Joe” Friday

Leading the Way Towards Modernization

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website. Reichenbaugh retired in 2018; we are indebted to him for undertaking this important project.

As the National Weather Service transitioned into the period of change and innovation known as the Modernization and Associated Restructuring, it became clear that strong leaders, visionaries, and those who valued teamwork would be essential to success. One of those was Elbert W. “Joe” Friday.

When Friday became Deputy Director of the NWS in the early 1980s, he was stepping into an agency in the middle of a massive overhaul. Efforts had already begun to prepare for the modernization, including a plan to integrate new technologies like Doppler radar, automated observations, and interactive computer systems. Eventually, Friday became the Director of the NWS, working to integrate those technologies into NWS operations as well as helping to develop an educational program to cross-train employees on how to use the new technology. Despite the many challenges and adjustments that came about as a result of the Modernization efforts, Friday’s role in developing/expanding use of technologies like NEXRAD and AWIPS, as well as his role in restructuring field office operations, helped to propel the NWS forward as an agency.

Here is an excerpt from his interview recorded January 2010:

On the success of the field office restructuring efforts:

“All of that then had to be put into place and so forth as a result of what we were doing. A long process, but when you take a look at the results, in my opinion, it was worth every bit of it. The accuracy of the weather warnings improved tremendously and they're still continuing to improve, as we learn more. The professionalism in the office has stepped up an order of magnitude; we’ve continued the training program so that we maintain currency across the board. It’s not a one-shot training activity and so forth. And in general, it turned out to be, I think, a very good process.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcript and audio recording of Elbert “Joe” Friday from January 2010 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/index.php/elbert-w-joe-friday

-

Full interview transcripts and audio recordings of Elbert “Joe” Friday from October-November 2020 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/index.php/elbert-w-joe-friday-0

Faith Borden

Here, in her own words, are those of Faith Borden, Meteorologist at the NWS Weather Forecast Office in Nashville, TN.

I have been interested in weather ever since I was a child. I lived in Massachusetts and my family and I were avid snow skiers -- one Christmas Eve, I was skiing and fell and broke my leg. While my bones were healing, it felt like I could feel the weather changing. When I told her, my mom told me I should become a meteorologist. Once I looked the word up in the dictionary, I knew that is what I wanted to do. Up until that point, I didn’t realize meteorology was a science -- all I knew was what I saw on TV. I thought those men on the news just made up the information. This was back when broadcasters were all male, chalkboards were still utilized for weather, and the local TV weather person did not have a degree related to a science field. I didn’t have much in the way of role models, but it didn’t matter. My love and interest in weather only grew from there.

In some ways, being determined to become a meteorologist made going through school easier for me. I knew I would need lots of math and science, so I made sure to take as much of those classes as I could when I got into high school. I didn’t have a guidance counselor to recommend classes, or path tracks like there are today. In some ways, this might have benefitted me, because I was not the strongest student when it came to math. I also struggled with reading, most likely due to having Dyslexia. It seemed I always understood the concept after the test, so my grades were just average.

Fast forward many years, and I was fortunate to graduate from Florida State University with a degree in Meteorology. While in school, I worked for a program that brought real-time POES satellite imagery into the classroom. As part of this program, I got to help develop curriculum for educators and help plan a weeklong intensive training program for teachers. This got me thinking about trying to merge education and meteorology. I was presented with an opportunity to go to grad school for science education, and you can say it has helped me get to where I am today.

In the 20+ years I have worked for the NWS, I have gone from intern to management, and back to a forecaster. Being a WCM in Las Vegas and Charleston was incredibly rewarding. I really enjoyed working with partners, developing exercises, educating/training others, and interacting and mentoring staff. I have been able to use my science education background and what I learned as a classroom teacher in my everyday career. However, balancing a career and raising a family can be challenging. It is not always possible to accommodate a working spouse in the city you end up in. Sometimes, sacrifices have to be made and one person has to travel in order to find employment. In order to support the education challenges of my daughter when she was young (she has learning disabilities and suffers with Dyslexia), and for my husbands’ job opportunities, I left the management position and was fortunate to get an internship -- and then to be converted by the 5/12 Involve Initiative to a forecaster in Nashville. A tough decision at the time, but one that has been well worth it!

An opportunity that came with being a WCM was getting one of the WCM representative positions on the NOAA Education Council. This has been one of the most rewarding opportunities! Being able to merge my love of education and forecasting has been simply amazing. In addition, I have learned so much about NOAA, the other line offices, policies/procedures, and how NOAA operates.

My vast experiences and many twists and turns that my career has taken have given me good insight into challenges that employees (especially women) can face while working for the National Weather Service. It is very difficult to have a work life balance while raising a family. I am passionate about education, excellent customer service, decision support, and diversity. I would not change anything about the career I have had and look forward to what the future may bring.

Kristine Johnson Nelson

Here, in her own words, are those of Kristine Johnson Nelson, currently a Meteorologist with the NWS Operations Center in Silver Spring, MD.

The day was Sunday, March 22, 2009.

I was covering the evening shift for my employee who was at radar school. Redoubt had been restless, but, up to that point, had only released steam and gas with very little ash. As I was finishing my shift, I noticed that the seismic signal got a little more active and persistent which, when combined with the latest Alaska Volcano Observatory statement that said an eruption could happen in hours to days, made me wonder if real eruptions would begin that night. I let the FAA Air Traffic Managers know that an eruption may be imminent, and told them to call me immediately if something happened. I found out later that they had laughed at me as soon as I was out of earshot, but when they called me 90 minutes later, they were all business.

I gave them initial guidance based on the forecast and locations of the flight tracks, and made my way into the office. I told them to keep the easterly tracks open into Anchorage, and shut down the rest. I think we kept planes coming in for at least two hours after the eruption before the volcanic ash was too close for comfort, and I advised them to stop the easterly track into Anchorage. I found out later that Carven Scott, who was Alaska Region’s ESSD Chief at the time, was on that last plane to make it through before the last track was closed. All the other planes had to turn around. Carven was very grateful!

Lou Boezi

Putting Computer and Technology Expertise to Work for the MAR

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website. Reichenbaugh retired in 2018; we are indebted to him for undertaking this important project.

While meteorologists make up a large percentage of those employed by the National Weather Service, the smooth operation of the agency relies heavily on experts from many different fields.

Enter Lou Boezi, a man experienced in computer technology and development who, after working with NASA, FEMA, and other prominent organizations, came to work with the National Weather Service in 1990. This moment in time was significant for the agency, as it was marked by massive transitions and overhauls known as the Modernization and Associated Restructuring of the National Weather Service. Working his way through a variety of different projects, including computerized Upper Air observations, the NOAA Weather Radio Project, and AFOS, Boezi ended up as the NWS Deputy Director during the Modernization era.

Here is an excerpt from his interview recorded in March 2011:

On the attitudes of National Weather Service staff during the transitions:

“The dedication of the staff was the strength, is the strength, of the Weather Service. It’s the local responsibility. It is the local sense of responsibility. This was a time when you saw an entire agency, from the lowest level to the highest level, intimately coupled in a task of joint interest.

“You know, we had organized national meetings of all the managers of the Weather Service. Never in history did we ever do that. We laid out these plans and we said, ‘This is what your responsibility and authority is going to be. And this is our obligation to you and your obligation to us. We do this for the good of the country.’ And this is for the benefit of the country. You know what you see locally and we had cost benefit studies done and all that kind of thing. So this was a smart thing to do for the taxpayers. There was a sense of pride and can-do and we can get this done, because they knew that these tools were helpful to them. And once that was the case, the demand-pull was just fantastic.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcripts and audio recordings of Lou Boezi from May 2010 and March 2011 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/index.php/louis-j-boezi

Mark Brown

Budgeting for the Modernization Era

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website. Reichenbaugh retired in 2018; we are indebted to him for undertaking this important project.

While much of the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring effort relied heavily on new technology, improvement of existing technology, and the streamlining of policy and procedure, those different elements all had one thing in common: a need for finances to get the job done. In order to make the modernization of the agency happen, an approved budget was necessary. This is where Mark Brown came in.

While serving as the Division Chief of the Department of Commerce Office of Budget, Mark Brown oversaw the formulation and advocacy of the NOAA Budget to Congress. From the early-70s to the mid-90s, Brown worked closely with NOAA Administrators and NWS Directors to come up with a way to execute the MAR that would also be approved from a budget standpoint, no easy task by any means. In order to gain a better understanding of what he would be presenting to Congress, he spent a lot of time understanding developing technologies like NEXRAD, equipping himself to answer important questions that could make or break the budget on the Hill.

Here are two excerpts from his interview recorded in August 2010:

On the approach to clearly defining what the MAR was meant to accomplish:

“I always like to quote [former National Weather Service Director] Dick Hallgren on this. He used to say ‘if we can agree on the policy on this we ought to be able to work through the details of it.’ And I think that’s what we did right early on, was to get policy directions set. So then it was a matter of what the market could afford and how fast we could move as opposed to trying to pick a new direction each time. And that certainly wasn’t easy, but it was worth it and great to see the result.”

On what he learned from living through the MAR:

“I think that we learned ... in terms of being at a higher level in the Department, that the staff that was there, the career staff, had a real responsibility to communicate with the new political leadership regardless of where they were coming from. And I think all the Secretaries of Commerce, regardless of affiliation, were willing to listen and to try and make sure they had a reasonable policy. While at the same time in a way trusting us to enforce a budget discipline so that we weren’t going overboard in what was being done.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcript and audio recording of Mark Brown from August 2010 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/index.php/mark-brown

Mary Glackin

Decades of Service in Advancing Modernization Efforts

Editor’s Note: In 2010, NOAA Office of Atmospheric Research Communications Director Barry Reichenbaugh recorded a series of oral histories with key researchers and others involved in the National Weather Service Modernization and Associated Restructuring, or MAR, during the 1980s and 90s. These oral histories have been republished on the Voices of NOAA website. Reichenbaugh retired in 2018; we are indebted to him for undertaking this important project.

As the National Weather Service moved into the massive transitional phase known as the Modernization and Associated Restructuring era, it quickly became clear that those with vision, determination, experience, and big-picture thinking would help to guide the agency through the coming changes. One of these individuals was Mary Glackin.

Glackin served in many different roles at the NWS, working as a meteorologist, a supervisory meteorologist, and a computer specialist before eventually assuming the role of NOAA Deputy Undersecretary of Oceans and Atmosphere. Over her decades of service to the agency, Glackin was heavily involved in several important projects like AFOS, AWIPS, and PROFS, all of which advanced the modernization efforts.

Here are two excerpts from her interview recorded in June 2010:

On the importance of having a clear vision for a program:

“I think one of the guiding things about the modernization was a very clear vision of what you’re trying - what we were trying to accomplish. And we really had a mantra, which is - was, you know, improve services to do that, by bringing together technology, improving the skill sets of our personnel, to be able to do that and improving observing capacity. So all of those pieces were in there and I think it really was the ingredients I think for a good program.”

On how it felt to work during the MAR:

“What a real kind of pleasure and honor it was for me to work on the modernization. I think it gave me a wonderful chance to work with some leaders that I think were very visionary. It gave me a chance to look at really an overall program that was put together so well, with people and technology and a very active communication outreach engagement component to it. And most importantly, it resulted in such a tangible result and benefit for the American Public. You know, so many lives saved and so many dollars as well.”

Resources and Additional Reading

-

Full interview transcript and audio recording of Mary Glackin from June 2010 available here: https://voices.nmfs.noaa.gov/index.php/mary-glackin

Ron Gird

Here, in his own words, are those of Ron Gird, a meteorologist specializing in education and outreach. Ron retired in 2017.

“Ever since I was a 5-year old child growing up in Boston, Massachusetts, I knew I wanted to become a meteorologist. I experienced two major weather events which determined my career in meteorology: a surprise thunderstorm at a family gathering and Hurricane Carol (1954) passing over our community.

I spent the summer of 1966 working for the NWS (then known as the Weather Bureau - ed.)at their northernmost weather stations, Resolute Bay and Alert, Canada, and it was then that I knew I wanted to work for the National Weather Service. I was a Junior at Penn State and applied to work at NWS as a summer student in their arctic weather stations. Spending the summer months with NWS full-time staff at these two stations gave me a real appreciation for the passion and excellence shown by the NWS staff while working in some of the harshest and most challenging environments on Earth. Regardless of the weather conditions, the NWS staff did their daily work with great passion and determination and got the work done correctly and on time, but most of all they really enjoyed their work. Never did I hear NWS staff complain about the challenging weather conditions they faced daily. I was thrilled when the staff invited me to help launch the daily radiosondes -- this was a real thrill. Meal time was a time to let loose and share daily experiences, the good, the bad and the ugly events of the day. In the land of the “midnight sun”, windows in the sleeping area were painted black in order to block out the sun. There was no local social life in these locations, only the staff on station for 24/7 every day for two months. Talking to the same staff every day could get boring at times.

I remember taking a flight to Thule Air Base, Greenland to pick up supplies for the upcoming winter months. Flying in this region had its special moments -- I recall our landing approach to Resolute Bay, sitting in the jump seat between the two pilots and all we could see was dense fog in front of us, but it did not phase the pilots at all. We never saw the runway until seconds before touchdown. The pilots shrugged it off as just another day at the office. I was so happy to be on solid ground once again!

Most memorable moment: the first time I could grow a beard, though no one thought much of it. Most of the staff grew beards. Additional moments to remember were visiting the local Eskimo village and learning how they survived such harsh conditions. Occasionally we would take hikes to tour the countryside and saw herds of muskox roaming freely.

My two months with NWS staff in the arctic region, filled with a lifetime of memories, was my defining moment for joining the NWS. The dedication and passion shown by the NWS staff was my inspiration to join the premier weather organization in the world. I was honored and thankful to work at NWS , enjoying every moment and every assignment in my career. No regrets.