Women in the Weather Bureau During WWII: Bessie Bergman Paul - National Weather Service Heritage

Women in the Weather Bureau During WWII: Bessie Bergman Paul

By NWS Heritage Projects Editorial StaffEditor's Note: The following first-person account of Bessie Bergman Paul first appeared in Women in the Weather Bureau During WWII by Kaye O'Brien and Gary Grice, 1991.

I was employed by the Weather Bureau from November 9, 1944, until June 26, 1981, with about a year and a half off - when I was released through a Reduction in Force (RIP) - the last half of 1953 and all of 1954. I worked for thirty-five years at Billings and one year at San Francisco.

Until December 1, 1949, I was Bessie M. Bergman. At that time I married Theodore E. Paul.

Why did I work for the Weather Bureau? It was probably in the genes. I was exposed to the needs of weather observations and forecasts at a young age from my father's association with aircraft, airports and airlines. He opened the airport at Lewistown (LWT), Montana, for Inland Airlines which had just changed its name from Wyoming Air Service. We lived at the airport there, and my father passed a test to take weather observations which he transmitted to the Billings Weather Bureau (it might have been considered a conflict of interest at the time.) At any rate, because I was interested in the weather observations, Dad taught me how to estimate wind direction and speed from a "wind sock." I also learned to read the "altimeter" from the "Kolsman" barometer. It wasn't called altimeter then, we simply said Kolsman. This was the pressure reading given at the time for aircraft landings. I also learned how to read a thermometer for current and maximum and minimum temperatures. As my Dad was the official weather information person for the city of Lewistown, the whole town called the airport to find what the temperature was, be it hot or cold. We had an extension of the office phone in our living quarters and the entire family would take turns answering the phone when Dad wasn't available or the office wasn't officially open. I remember answering the phone one evening when it was quite cold and receiving a request for the current temperature. I replied, "minus eight" only to have the additional query, "Is that above or below zero?"

Before starting work with the Weather Bureau I was a high school graduate with four full years of mathematics including College Algebra. I also had four full years of science including General Science in Jr. High and biology, chemistry and physics in High School.

As a result of my excellent grades, particularly in the foregoing subjects, I was offered a scholarship in Pharmacy at the University of Montana in Missoula. I decided to see if I would like drug store work so I applied for and obtained a position at what was then Bennett's Drug Store (1944.) It was while working there that I learned that the Weather Bureau needed new employees. While on shift one day at Bennett's Drug Store, a gal whom I knew from chemistry class in school came in to cash her check. It was a government check for about $125. We got to talking, catching up on what had happened since graduation and life in general. Just before leaving, she said to me, "Hey, Bess, you like this kind of "junk" that has a lot of math and science in it, why don't you come up and apply for a job? They are hiring now." Needless to say, I was up at the airport to secure an application form the next day. The $125 was an incentive, also, as I was only earning $50 a month at Bennett,s.

The Weather Bureau provided excellent training. I, of course, had on-the-job training. The Head Observer was a former school teacher, as were many Weather Bureau employees at this time, and she had constructed an outline to be used as a study guide for Circular "N". I really feel it was the Head Observer who started me off with the right attitude toward my work. She set such high standards and instilled in me such pride in the work I was doing and a deep sense of loyalty to the Weather Bureau and "My Country" that carried through for me until the day I retired.

My acceptance by Weather Bureau employees was outstanding, especially by the observers. A few of the forecasters were a little stuffy and much impressed by their P-ratings. I, of course, had an SP-rating when I started working and there was a sense of a caste system between P and SP employees. I think I was a little in awe of all the goings on, but I was impressed by the precision, competence, and intelligence of the people who were later to become my friends and cohorts. The morale on the station was very high, superb, in fact.

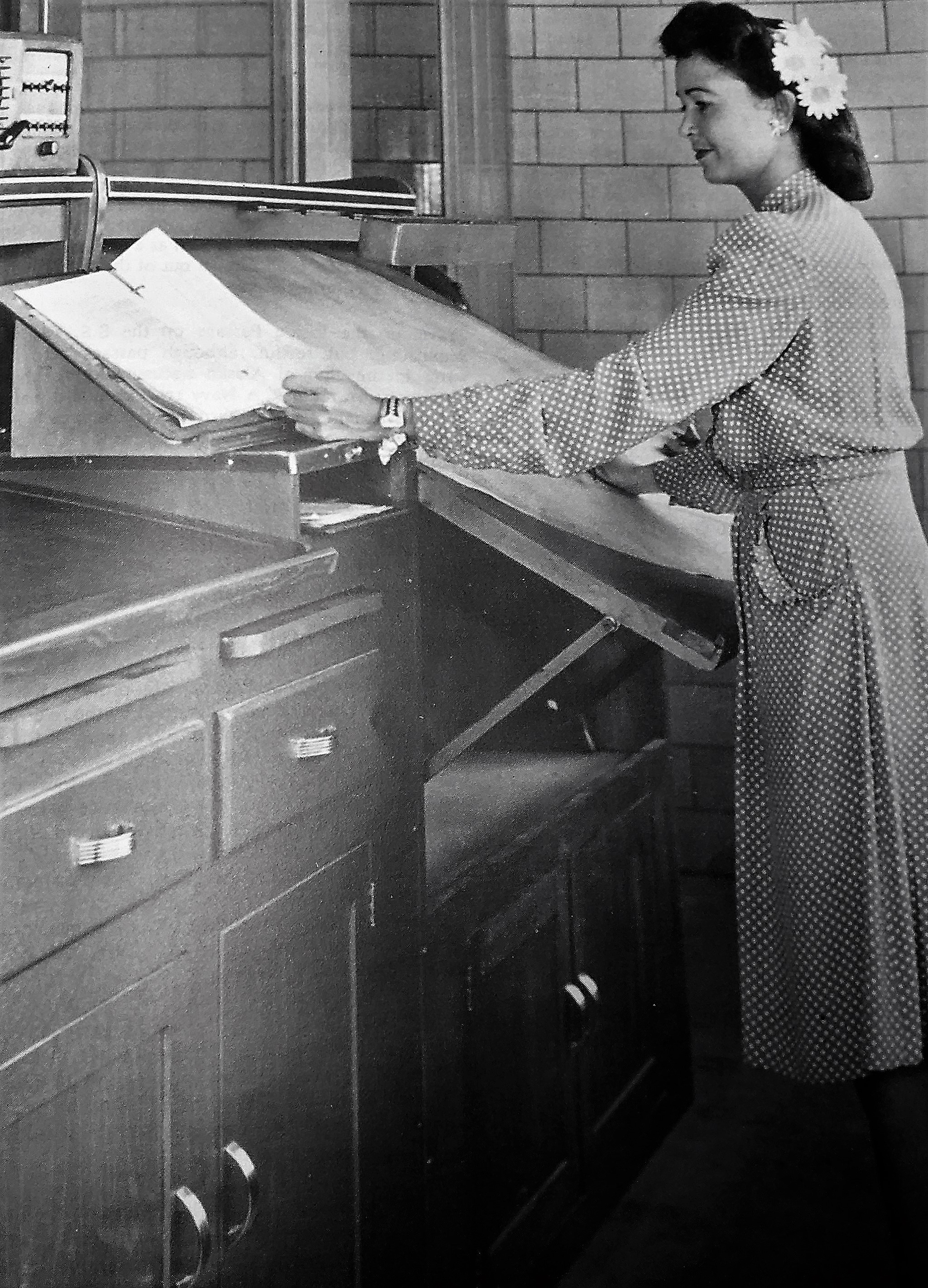

My primary duties were to take and record weather observations, which were statutory regulations as far as the Weather Bureau was concemed. I also took PIBAL observations, answered phones, sent ceiling balloons, typed forecasts and sent them over TWX and Westem Union. I changed the charts on barographs, thermographs, and rain gauges to mention a few. I checked the water each week in the batteries of the triple register. One fun thing and probably why the female employees were encouraged to wear slacks; we climbed the 33 or 34 foot pole atop the Ad Building on which was perched the anemometer to read how many miles of wind had blown by Billings every Monday morning at 9 a.m. We changed the 75 pound helium tanks when necessary, we changed the ring setting on the sunshine gauge in season, you name it, we did it, because that was part of the job.

In 1944, Billings was a forecast center and we had an administrative staff plus forecasters and observers. The forecasters and admin employees were all men except for the secretary. The observation staff was all female. Out of twenty five people, I suppose about eight were female.

I entered on duty as an SP-3, November 9, 1944. This was the year I graduated from high school and I was 18 years of age. My salary was $1440.00 per annum and we were paid once a month. We did a little better than this as we got some overtime on those 54-hour weeks. I felt like I was very rich because I had almost tripled my wages from the drug store.

I was on rotating shifts. We worked six weeks at a time on the same shift. We had a variety of shift beginnings and endings. The hours were mainly set up to handle the synoptic and PIBAL observations smoothly. Particularly the PIBALs, because two people on PIBALs ensured a speedier run for plotting and encoding. Mainly I worked 8 and 9-hour days. We routinely worked 48 and 54-hour weeks.

The high point in my career other than when I was first hired was when I passed the test for GS-7 and was allowed to remain in Billings as an observer-briefer when the Forecast Center moved to Great Falls. This was April 1, 1953.

In working for the Weather Bureau during World War II, I felt patriotic and important. I felt I was very much a part of the war effort and felt very good about it. Yes, I would do it again! I believe it was my destiny and I was born to do this type of work. I truly enjoyed my work and the time I worked was gone before I knew it. It seemed much more like days than years that I worked, even considering I worked shifts.

I feel that by my work I proved that women were just as capable of doing this job as men. In fact, more capable in some cases. I also, at the time, released a man to go fight at the front and this was part of the hype of going to work for the U.S. Government at that time.