Signal Service Reflections - National Weather Service Heritage

Signal Service Reflections

By NWS Heritage Projects Editorial StaffEditors note:

The following stories were obtained from The Beginning of the National Weather Service: The Signal Service Years (1870-1891) as Viewed by Early Weather Pioneers edited by Gary K. Grice.

H.B. Boyer:

One of my assignments was at the New Orleans Signal Service office, and I must confess that the assignment caused me no little alarm. In view of the fact that although four years had elapsed since the terrible yellow-fever epidemic of 1878 had swept the lower Mississippi Valley, it was still the topic of conversation, and there was an epidemic of the disease then at Pensacola. On the way to New Orleans our train stopped at Pensacola Junction where I saw men patrolling the station platform with shot guns on their shoulders, and was informed that it meant a “shot-gun quarantine” against Pensacola. Naturally, this incident failed to cheer my faltering and depressed spirits.

I was stationed at New Orleans about three years, including six months in charge of the station at Port Eads where I had the pleasure of meeting James B. Eads, the great engineer who constructed the St. Louis bridge and the Mississippi jetties. The Port Eads station was discontinued under me, and while awaiting instructions, I received a note from a friend who informed me that orders would soon be issued for me to proceed to Key West, Florida.

I was nearly panic stricken. It should be understood that at that time Key West was commonly looked upon as being a hot-bed of yellow fever which, I was told, was endemic at that place and that to the unacclimated, death was certain.

On learning of my probable assignment, my friends gathered around me with lugubrious and sympathetic faces, and recounted the most horrifying tales of the great 1878 epidemic - stories that congealed my blood, and at night, made me spring up in bed and cry out in terror with nightmare. And they denounced in unstinted terms a Government that would heartlessly and cold-bloodedly and brutally send its servants to certain death!

In consternation I hastily composed a long telegram to my father in Washington, D.C. Through the influence of Senator Don Cameron of Pennsylvania, my orders were revoked and I remained at New Orleans.

D.G. Benson:

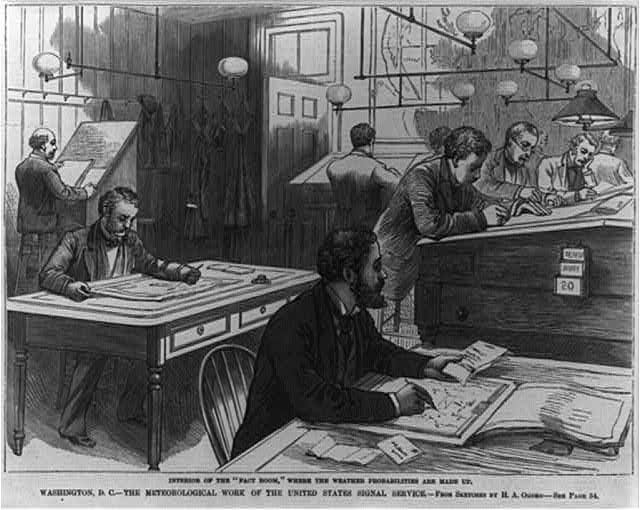

My early experiences in the Signal Service were so strongly impressed upon my mind that I can readily recall as if it were yesterday in outline of the offices on both

sides of G street [Signal Service weather office in Washington, D.C.], the divisions and rooms, the faces and names of scores from General Greeley down to the

recent and awkward recruit. Some of these are gone and others are among the leaders of today. It was the military spirit that impressed one, to which one became attached, and it is this spirit of the old Signal Corps that is the backbone of the enlarged Weather Bureau service of today.

What would a young assistant observer of today think of being ordered to take charge of a station like Savannah for six months after having been on station for seven weeks? This fell to my lot and my assistant had the extended experience of three weeks less than myself. This happened as a result of the epidemic of yellow fever at Jacksonville. It was in mid-summer and no relief was sent until after freezing conditions in December. In the preceding epidemic, both men stationed at Savannah died at the post of duty.

Ford A. Carpenter:

On the treeless levels in Wyoming - then a territory - a rainmaker appeared. He “contracted” with the ranchers to “make” so many inches of rain for so many thousand dollars an inch. He erected mysterious funnels projecting out of dilapidated tents. All this aroused the righteous indignation of the old Signal Sergeant. He rushed into print, filled the little cattle county paper with outbursts against the rainmaker and his promise. The rainmaker said nothing but waited for the long promised rain. The sergeant became as abusive as the paper would print. This was too much for the straight-shooting cowboys. They practiced gunplay on the sacred Signal Service’s whirling anemometer cups, shooting them up as fast as new instruments were replaced by the frightened sergeant. They shot his rain gauge full of holes, and as a last indignity, they caught the sergeant one night and hung him to a big brass hook in his own office by the slack of his trousers. And then, against all official forecasts, the first rain in six months came down in torrents!

Norman B. Conger:

When you look at the six fine rooms I have now [1922] with fine office furniture, rugs on the floor and all things neat and tidy, you just stop and wonder what the boys of those days would think of us with such luxuries as we have now.

There was the observer in charge, and one assistant, and the printer on the station. I was expected to take the 6:36 a.m. observation and stay on until after the sunset observation. On Saturday nights, I remained until after “Goodnight” after the 10:36 p.m. observation was taken and filed. Then we had about 40 substations for storm warning display, and when we got an order, we made forty copies of it and filed them at the telegraph office. When replies were received from the 40 substations, we telegraphed the Central Office [Washington, D.C.] with a message something like this, “Storm warnings up received at 1:10 a.m.” After the Central Office was notified, we could go to bed, but it was mostly about 4:30 a.m. when the last reply got in and you had to be on the job again at 6:00 a.m.

This was quite the regular thing during the season of navigation, and we just went along and did the work required, because we were soldiers, and to obey orders was the first to consider and sleep came later. How would our men of today like such conditions?

John S. Hazen:

There comes to mind now the one told on Hayden when he first went in to the service of how he was found locked in a closet and down on his knees praying for support after having broken every thermometer but one on the station. It seems he had started to whirl the maximum and the psychrometer at the same time with the result that every thermometer in the shelter was broken. He rushed to the office and while making his selection from the remainder managed to step on three more.

Likewise, the following on the man from Texas who could not get a leave to go fishing but went anyway. He made an artistic series of six observations coded same and filed in Western Union, first carefully explaining to the clerk that he was to send them in serial order one each morning at seven a.m. The man then starts on his fishing trip unconscious of the workings of fate.

The clerk carrying with him the careful explanation of how to send these messages was called away the next day. A new clerk finding the bunch on his desk the following morning fired the whole lot in. Result; an Inspector with a lieutenants uniform and proper credentials waiting at the door for him when he returned. A trying hour for Mr. Texas and a shift in scenery.

C.F. von Hermann:

At La Crosse [Wis.] the temperature once fell to 43 degrees below zero, a temperature I had twice experienced before in Wyoming. On this occasion the circumstances were somewhat peculiar. At night when I went to bed I did not care for a fire, but I liked to get up in a warm room, so I always had a fire laid in my room in the afternoon, which I would light in the morning, and then remain in bed until the room was comfortably warm. But on this particular morning when I got up it did not seem to me to be cold enough even for a fire in my room, and I got up and dressed without the least discomfort; wore my overcoat downtown wide open, and no gloves and yet experienced no inkling that it was very cold, and was supremely astonished to find all the mercurial thermometers frozen and the alcohol minimum registering 43 below zero. Fog prevailed at the time, and I wondered why the fog particles did not freeze; they did not appear to be frozen, though settling on objects in the form of thick frost work. I have never been able to explain why on this occasion I did not experience a sensation of cold, but was perfectly warm and comfortable, until I had read the thermometer.

J.W. Smith:

While “on station” there were some amusing experiences and a few very unusual ones. One of the former was experienced by my predecessor at a small southwestern station at Corsicana, Texas. He told me that soon after establishing his station he was waited on by a committee, appointed by dissatisfied citizens on account of the very unsatisfactory weather conditions caused by the meteorological instruments as there had been no such weather before “them things were set on the roof”. All the explanations that could be made proving unsatisfactory, the official suggested they adjourn to the cafe over the way for further discussion, where it cost our man about $25 for sufficient refreshments to convince the committee that the weather instruments were not at fault.

Even in the early days of the service, visitors often came to see how the weather was made, particularly at stations in large towns and cities. More than a few times I have heard surprise expressed at the small size of the instruments, their insignificance. Not a few expected to see quite massive machinery laboring, groaning and belching, for as they thought devices that couId record great gales, hurricanes, and storms must be large and complex. Visitors have so stated to me, and expressed disappointment at the quiet, silent method in which the instruments do their work. Few after seeing and having the instruments explained would fully comprehend them.