On the Front Lines of Change: The Women of the Wartime Weather Bureau - National Weather Service Heritage

On the Front Lines of Change: The Women of the Wartime Weather Bureau

By Emily Senesac (emily.senesac@noaa.gov)In 1917, amidst the international armed conflict of World War I, the culturally-attributed roles of American men and women became increasingly distinct and clear. It was universally known at that time that men were the breadwinners of society: they worked, they earned, and they left it all behind to defend their country. Women, on the other hand, belonged at home with their families -- contributing to the war effort with canned food drives, victory gardens, and hand-sewn clothes was all society permitted them to do. While some women joined the workforce, public opinion was fiercely against their “insistence” on taking away from male breadwinners. Thus, the majority of women chose to remain where they thought they belonged: out of the way.

By the time the United States entered World War II more than two decades later, attitudes about women could not have been more different. In the aftermath of the Great Depression, many American families were still struggling to get back on their feet. This basic economic need to provide for their households drove women towards employment outside of the home. Although sectors of society still viewed this behavior as unacceptable and selfish, many employment recruiters and members of the media took a different approach. Instead of shaming women for wanting more, they played on female patriotism, emphasizing the need for the “self-sacrifice” of employment in order to preserve the American way of life and bring the troops home. As a result, the early 1940s saw the female workforce grow by more than half -- in civil service fields alone, the workforce expanded by 540%.

As women began to enter the working world, it became clear that the traditionally “masculine” jobs had the most to offer in terms of compensation and opportunity -- especially when compared to the more “feminine” jobs of waitressing, sewing, and the like. Over time, more and more women came to this realization; massive shifts occurred in the labor force as women abandoned the traditionally “female” occupations. According to women of the era, this wartime work completely changed how they felt about themselves. In fact, several women remarked that being able to “hold their own” with men improved their perceptions of their own competency and worth. Finally, at this moment in history, they felt of value outside of the home. This outright change in attitude was far-reaching, becoming apparent even to the higher-ups in the national government. Harold Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior at the time, vocalized the newfound confidence of women, saying “I think this is as good as any...to warn men that when the war is over, the going will be a lot tougher, because they will have to be compared with women whose eyes have been opened to their greatest economic potentialities.”

Having realized the extent of their capabilities, women became a force to be reckoned with, particularly in the wartime Weather Bureau

The movement away from “traditional” female occupations and towards more “masculine” ones meant that women were engaging with the fields of manufacturing, technology, and science -- meteorology falling into that final category. It was a slow yet steady transition: at the time of the Pearl Harbor bombing, only two women were working in the observation and forecast staff of the Weather Bureau. However, in 1942, the Weather Bureau issued the following announcement:

OPPORTUNITY FOR WOMEN IN METEOROLOGICAL WORK

"Although there has been much prejudice against and few precedents for employing women generally for professional work in meteorology, perhaps a dozen women have obtained meteorological positions in the last few years, mostly outside of government service. However, since there is at present an acute shortage of both trained meteorologists and men for observers and clerical positions in the Weather Bureau and other government agencies, airlines, etc., women with the proper qualifications (same as for men) are now being welcomed into many places where they were not encouraged even last year (in England women have already taken over many meteorological posts, we hear). Therefore, women with training or experience in meteorology or its branches should apply immediately for any of the current or forthcoming U.S. Civil Service examinations in meteorology which are open to them...This will be an opportunity to join the vanguard of the many women who will very likely find careers in meteorology in the not-too-distant future and at the same time it will be a patriotic choice in case the war should require many women to replace or supplement men as meteorologists."

By 1945, more than 900 women had found jobs in clerical work or as junior observers in the Bureau nationwide. From there, that number would only continue to grow.

While most female employees remembered being “well-received” by their colleagues, many said there were always one or two men who had doubts about their capabilities. Grace D. Harding, who worked at the Bureau for four years, remembered that “...seasoned male observers had some reservations about [her] ability, but they were very cooperative...Being female in a 98% male situation helped to break the ice.” Despite a few resentful colleagues, most of these women say that collaboration, teamwork, and morale were absolutely outstanding.

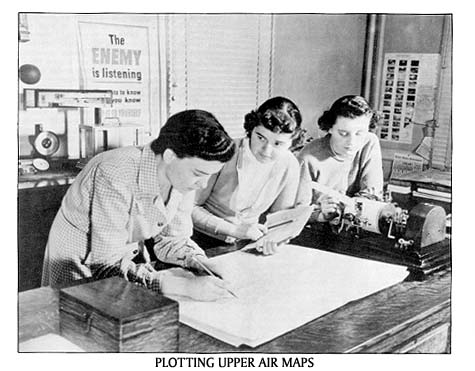

At the time, most of the work that women did for the Weather Bureau involved taking upper air and atmospheric observations, plotting maps and charts, and communicating with pilots regarding flight plans and weather concerns. However, many of these admirable women took their jobs very seriously, believing that their contributions to the war effort had a significant and lasting impact. Dorothy Hurd Chambers, a woman who worked at the Weather Bureau from 1944-1948, reflected proudly on her experiences and the enduring influence that women at work had on society: “We girls, mostly in our 20s, walked or drove to our jobs all over the country in all kinds of weather, all hours of the day and night. We learned to make the vital weather observations that the pilots depended on. Mere girls decided when planes could take off or land...We girls showed the world that ‘man’s work’ could be women’s work, too.” That relentless determination and pride in their achievements solidified the eternal presence of women in Weather Bureau history, right alongside the men. However, that isn’t to say that these women sought to contribute in the same way as their male counterparts. Charlotte Schmidtke Jones, a 23-year employee of the Bureau, explained “My contribution was always that of a woman--I never wanted to be a man.”

With their newfound confidence and sense of purpose, the remarkable women of the wartime Weather Bureau made their own mark on society and on the functioning of a major government agency -- a mark that would last for generations to come.