Flying Kites for Science - National Weather Service Heritage

Flying Kites for Science

By Chris Geelhart (chris.geelhart@noaa.gov)Early in the history of the agency, the Weather Bureau recognized that measurements of the upper atmosphere were critical to expand the science of weather forecasting. Willis Moore, the Chief of the Weather Bureau, wrote in his annual report in 1895:

"It is, therefore, highly essential to push forward such lines of scientific investigation as give the greatest promise of fruition. For twenty-five years we have been making readings at the bottom of the great ocean of air, while many believe that the subtle forces which combine to initiate storms and the constant accretion of forces which augment their energy as they move eastward, or which at times cause them unexpectedly to be dissipated after having reached a great degree of storm intensity, may be operative at great elevations. It is therefore desirable that upper air readings should be accomplished by this Bureau to determine the accuracy of these theories, and that synoptic charts baaed upon readings at an elevation of not less than two miles should be prepared, showing the conditions prevailing at that altitude throughout a considerable portion of the country. The difficult is to devise appliances, which, while captive, will carry automatically recording instruments to the proper elevation under all conditions of wind velocity and variable direction; but the obstacles do not seem to be formidable, and it is believed that they can be successfully overcome."

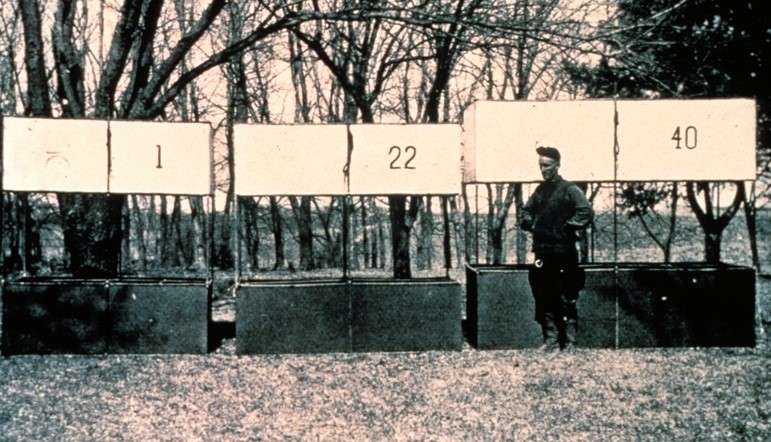

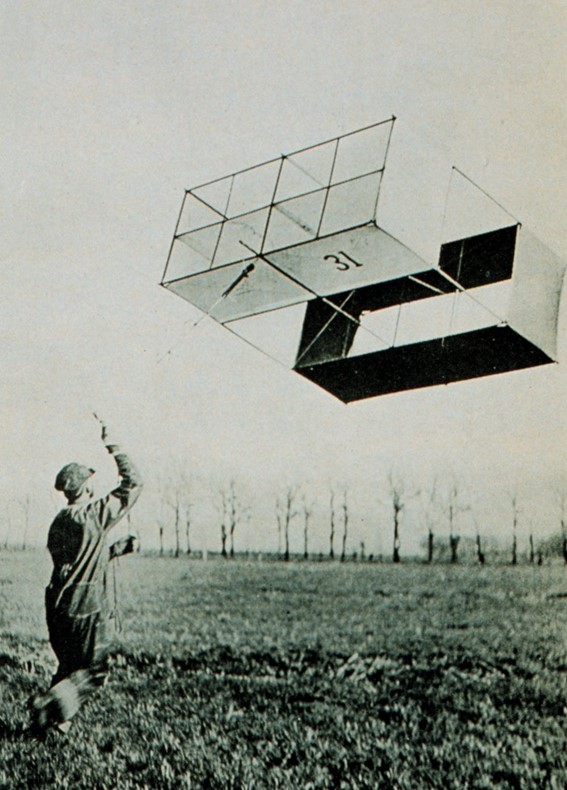

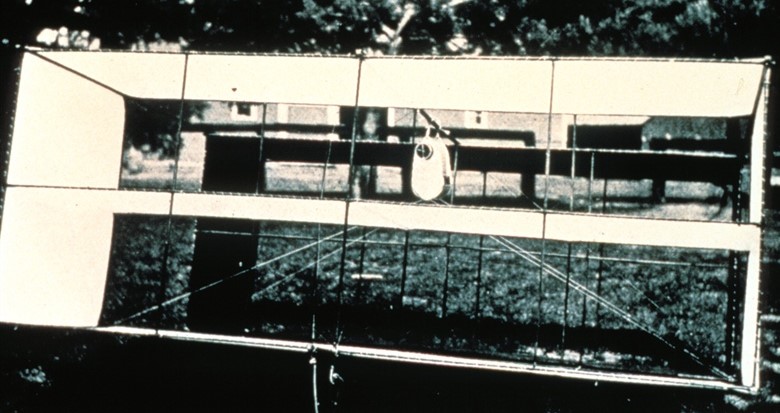

Professor Charles F. Marvin, in charge of the Weather Bureau's Instrument Division (and later Chief of the bureau), was directed by Moore to study methods for sustaining automatic instruments at high elevations. Early efforts by William Eddy at the Blue Hill Observatory near Boston in 1894 used five kites tethered together to reach a height of 1,400 feet. Marvin's work utilized a box kite design by Lawrence Hargrave, tethered to the ground by piano wire. One such flight reached a height of 7,000 feet.

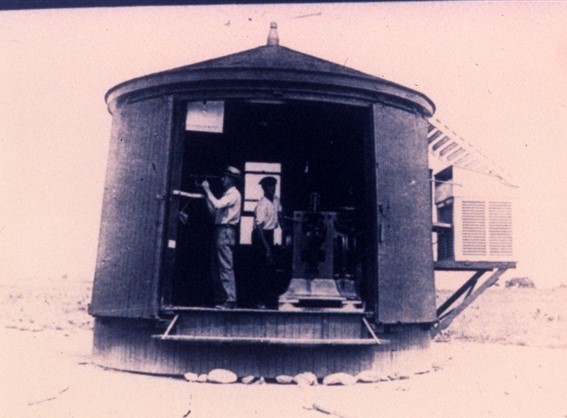

It was recognized that the strength of the wind would be a highly variable factor in kite heights. Early use of captive balloons to reach the desired height proved to be of little use, and tests using both kites and balloons were also unsuccessful. These factors were key in development of the Mount Weather Research Observatory in the early 1900's, where balloon usage was thoroughly explored.

tether for the kite.

While research continued into the use of balloons, kite stations were established at six locations in 1918 in the central and eastern U.S.: Ellendale, N.D., Drexel, Neb., Royal Center, Ind., Groesbeck, Tex., Leesburg, Ga., and Broken Arrow, Okla. Another site was added at Due West, S.C., in 1921. Kites were flown daily, and when possible, continuous series of flights covering periods of 24 to 36 hours. Several of these stations had been operated by the Signal Corps during World War I to take observations using small "pilot balloons," and these were transferred to the Weather Bureau.

Kite flying had its hazards. An observer at Ellendale was killed by a lightning strike during a flight. The March 1926 issue of Weather Bureau Topics and Personnel reported that at Royal Center on February 21, seven kites, with six miles of wire, broke free and landed 190 miles to the northeast.

By the mid 1920's, efforts began to shift to using airplanes in place of kites. They could reach a greater altitude than the kites, though there was still an altitude limit due to open-air cockpits. The tethered kites also proved to be a hazard to aviation, which was undergoing significant expansion. The Drexel station was closed in May 1926. The Groesbeck, Royal Center, and Broken Arrow kite stations discontinued their observations on June 30, 1931; regularly scheduled meteorological aircraft flights began the next day in Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, and Omaha, and in Atlanta in July 1932. Due to the lower amount of aviation activity, the Due West and Ellendale stations initially remained operational. However, Due West was closed in June 1932. The last holdout, Ellendale, was closed in June 1933 after an airplane station was established at Pembina, N.D.

For more information, check out the following links: A Brief History of Upper-Air Observations (NWS Headquarters), NOAA Photo Library's collection of kite and weather balloon photos.