Crossroads in Weather History – The Pioneers - National Weather Service Heritage

Crossroads in Weather History – The Pioneers

By Greg Romano (gregory.romano@noaa.gov)Our Story

Since the earliest days of our young nation, fascination with the weather has been a constant. This is not surprising given the pioneering, self-reliant nature of the first settlers and the colonists who would soon follow.The nation’s founders shared this fascination -- Thomas Jefferson’s daily weather observations are well documented, and Benjamin Franklin’s thunderstorm kite experiments are legendary.

As the 19th century unfolded, men and women of science continued to explore the many ways the natural world worked. In 1821, William Redfield (left), a self-taught scientist and merchant who would become the first president of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science, traveled across central Connecticut and western Massachusetts after what became known as the Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane. He observed trees that had fallen in opposite directions in the two states. It would take him a full decade to publish his theories about storm rotation, “On the Prevailing Storms of the Atlantic Coast,” in the American Journal of Science and Arts in 1831. At the time, this was a controversial position to take.

Shortly thereafter, James Pollard Espy espoused the convective theory of cyclones and gave presentations to several of the top international scientific societies of the day, eventually publishing in 1840. As the federal government’s first meteorologist (to the War and Navy departments), Espy promoted the use of the telegraph to collect weather observations and studied the progression of storms that formed the basis for scientific weather forecasting.

A controversy developed between Redfield’s and Espy’s conflicting theories, enhancing scientists’ interest in exploring meteorological phenomena.

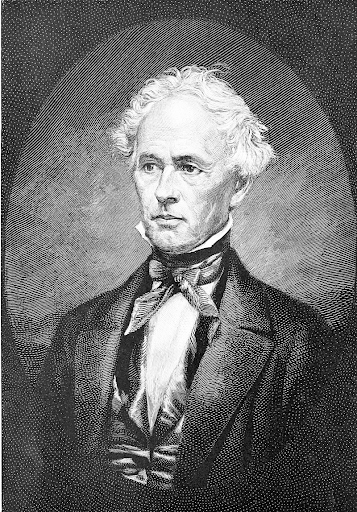

Professor Joseph Henry (right), first Secretary of the Smithsonian, was an early experimenter with telegraphy and had a vision of using data collection for climate studies and forecasting. By 1849, Henry had persuaded telegraph companies to transmit local weather data to the Smithsonian, By 1857, telegraph stations from New York to New Orleans were sharing observations for climatological studies.

collection for climate studies and forecasting. By 1849, Henry had persuaded telegraph companies to transmit local weather data to the Smithsonian, By 1857, telegraph stations from New York to New Orleans were sharing observations for climatological studies.

Henry would also play a role in presenting the work of one of the nation’s early women climate scientists, Eunice Newton Foote. In the 1850s, Foote demonstrated the ability of atmospheric water vapor and carbon dioxide to affect solar heating. The results of her experiments were presented to the American Academy for the Advancement of Science in 1856, but not by her … it was not considered proper in those days for a woman to be involved in science, so Prof. Henry presented the information!

At about the same time, self-taught Wisconsin naturalist and scientist Increase A. Lapham was also picking up the mantle for the use of real-time data to provide warnings, mostly directed at saving the lives of those crossing Lake Michigan as a “public good.” In 1850, he urged the “establishment of an observatory where forecasts could be collected at the lake ports.” In 1860 and 1861, Lapham worked with Dr. Asa Horr of Dubuque, Iowa to make a series of simultaneous observations three times a day to prove that storms could be tracked from west to east and to predict squalls for the Great Lakes. In February 1861, Prof. E. T. Caswell of Providence, Rhode Island provided charted comparison data. The diagrams served to arouse general interest at the Wisconsin State Fair, at the Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce, and in other public places, raising public awareness about the ability to predict storms. An original of this map that shows the progression of what we know today as isochrone lines of the storm fronts is archived in the vaults of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

The Civil War interrupted these early efforts. However, shortly after the war, Henry called for the federal government to establish a national weather service. In 1867, Lapham exchanged correspondence with J. D. Hooker, director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, London, about successes Great Britain had achieved in their attempts to predict storms by means of telegraph.

It was also around this time that Cleveland Abbe, the new head of the Cincinnati Observatory and supported by the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce, foresaw the benefits of applying forecasting (which he called “probabilities”) to serve the needs of commerce. For a three-month period in 1869, Abbe collected telegraphic weather observations and published his “probabilities” in the Cincinnati Weather Bulletin.

In the waning days of the 1860s, these forces converged in surprisingly quick fashion, resulting in the creation of a federal service that was the forerunner to today’s National Weather Service.

Stunned by a bad shipwreck in November 1869, Lapham, acting on his beliefs that the loss of lives on the Great Lakes could be prevented through forecasting efforts, reached out to a friend serving as a representative of the National Board of Trade urging action. A week later on December 8, he submitted petitions and memorials to Wisconsin Congressman Halbert E. Paine, urging the establishment of a government weather service.

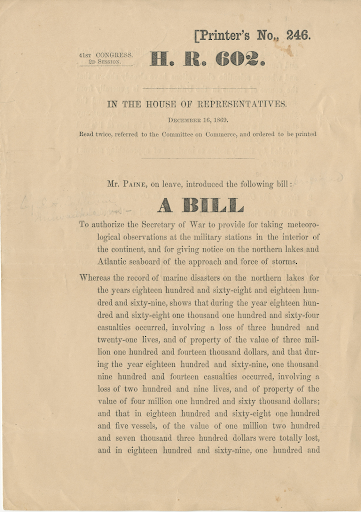

Congressman Paine, once a student of Elias Loomis, quickly recognized the need for the weather service and introduced a bill before Congress on Dec. 14. A revised bill -- H.R. 602 -- was presented two days later. Paine recognized this service would require a disciplined approach to taking observations at the same time every day and to transmit the observations reliably and consistently.U.S. Army Chief Signal Officer General Albert J. Myer appealed to Paine to place the proposed service under the Signal Service. Apparently swayed by Myer’s enthusiasm, Paine chose the U.S. Army Signal Service as the home of the first national weather service.

Congressman Paine, once a student of Elias Loomis, quickly recognized the need for the weather service and introduced a bill before Congress on Dec. 14. A revised bill -- H.R. 602 -- was presented two days later. Paine recognized this service would require a disciplined approach to taking observations at the same time every day and to transmit the observations reliably and consistently.U.S. Army Chief Signal Officer General Albert J. Myer appealed to Paine to place the proposed service under the Signal Service. Apparently swayed by Myer’s enthusiasm, Paine chose the U.S. Army Signal Service as the home of the first national weather service.

Paine reintroduced the bill as a joint Congressional resolution in early February, which was adopted by unanimous consent, referred to the Committee on Military Affairs where it left without amendment, passed the Senate, and was sent to the White House ... all within a week. It was quickly signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant, thus establishing the first nationwide weather service on Feb. 9, 1870. Gen. Myer was assigned to oversee the new federal weather organization, becoming the first director of what was officially known as the Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce.

References:

- Aviles, L B., 2018: Taken by Storm, a Social and Meteorological History of the Great New England Hurricane, American Meteorological Society. 265 pp.

- Bergland, M. and P.G. Hayes, 2014: Studying Wisconsin: The Life of Increase Lapham. Wisconsin Historical Society Press. 258 pp.

- Fleming, J. R., 1990: Meteorology in America, 1800-1870 The Johns Hopkins University Press. 264 pp.

- Lapham, I. A., 1850: Transcribed Letter to The Honorable Senate and Assembly of the State of Wisconsin, Increase A. Lapham Papers, 1925-1930, Wisconsin Historical Society, Box 4, Folder 3, Chapter XXI: Storm Signals 1850-1872, p. 1-7.

- Potter, S., 2020: Too Near for Dreams: The Story of Cleveland Abbe, America's First Weather Forecaster. American Meteorological Society. 374 pp.

- Whitnah, D. R., 1961: A History of the United States Weather Bureau, University of Illinois Press, 267 pp.