As great as is to use data from the Geostationary Lightning Mapper, there is an important caveat forecasters have to consider when using the data.

During the afternoon of July 11, typical “air mass” showers and thunderstorms were developing across northern Alabama, including several south of the Huntsville International Airport. At 12:18 PM CDT, the GLM Flash Extent Density data started to light up with these cells, including one larger flash at 12:21 PM. (Huntsville airport is marked by the eastern concentric yellow circles.)

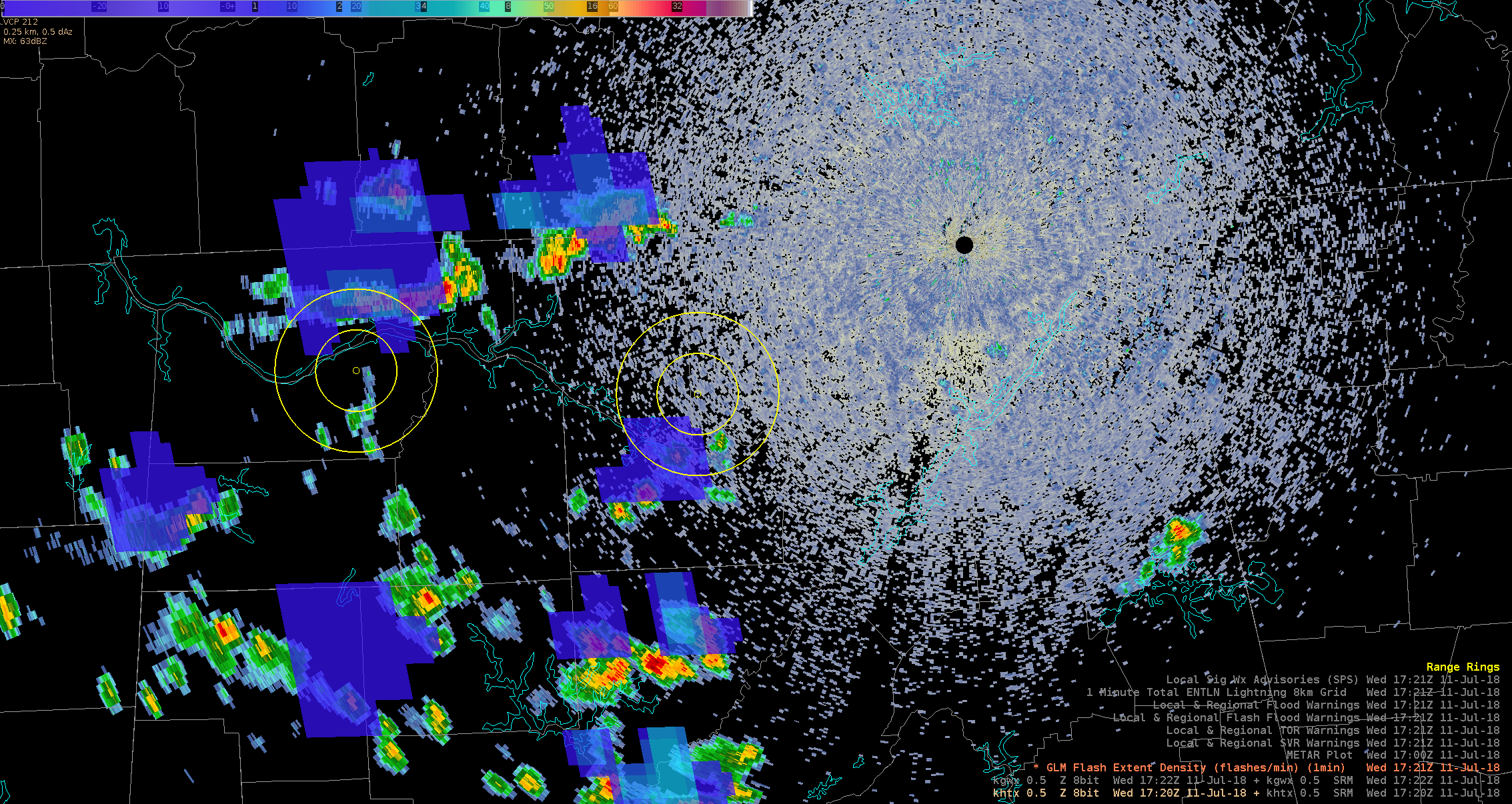

KHTX radar valid 1722 UTC 11 July 2018 and GLM FED valid 1721 UTC

As I’ve noted before, we issue airport weather warnings for Huntsville if lightning is within 5-10 miles, heading towards the terminal. So forecasters were justifiably alarmed that GLM flashes were starting to show up within the 10-mile range ring, and just barely edging towards the 5-mile ring.

But here is where that caveat comes into play: the parallax effect. Radar showed the actual echoes associated with these flashes to be well to the south of the GLM flashes. Earth Networks Total Lightning data from the same time period showed lightning confined to these cells well outside the 10-mile range ring. Furthermore, the cells were moving away from the field.

KHTX radar valid 1722 UTC 11 July 2018 and Earth Networks total lightning valid 1721 UTC

It’s worth noting that GLM showed a greater spatial extent during some of these flashes, but Earth Networks was much closer in location to the radar.

So while a cursory glance at the GLM data might lead to an airport weather warning, it was important to double-check GLM against the radar–and recognize that an AWW was not necessary in this case. The same caution will need to apply as we begin applying GLM to other public safety situations.

Re-posted from: https://nasasport.wordpress.com/2018/07/11/glm-public-safety-an-important-caveat/